06 Jun Monasteries of Meteora, Greece

In the chapel of St. Stephen’s Monastery, set high among the giant outcroppings of rock that stand before the Pindos Mountains in central Greece, the nuns’ chanting of Vespers goes on and on as evening turns into night. Their voices, singing in a minor key of mournful solemnity, become a drone, the unfamiliar sounds an incantation.

The nuns themselves, draped in black cloaks, their faces framed with severe black bands, sit motionless or move about freely from one icon to another–strange, fearsome paintings of Christ, Mary and various saints– across the top of the chapel. Lighted candles hang from brass chains.

There is no other light–only shadow, and black figures moving, and incense hanging sweet and thick in the air, and a heavy feeling of enclosure. Sleep begins to overtake me, despite the discomfort of the hard benches we’re sitting on. To shake myself awake, I shift my body and cross my legs. Immediately, a nun glides over to me, gives a light tap on my knee, motions with her hand, and looks at me with deep blue eyes. Her face is a mixture of kindness and unquestioned authority. Like a child caught in mid-mischief, I uncross my legs. And the chanting goes on and on…..

Her face is a mixture of kindness and unquestioned authority

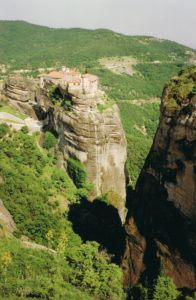

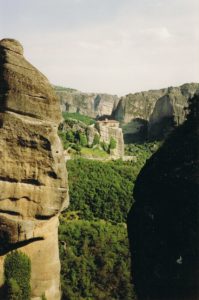

Later, in the nearby town of Kalambaka, we sit in the taverna drinking wine. Red and white checkered cloths cover the tables, and pictures of blonde American movie stars line the walls. In the darkness outside loom enormous rocks, called Meteora, a name derived from a word meaning high in the air. Bare and grey and phallic-shaped, they stand like a monstrous fortress.

Hidden among them, as if suspended between earth and heaven, is a series of medieval Greek Orthodox monasteries. A handful of these, including the one where we’ve just attended Vespers, are still inhabited. This is desert land, the abode of ascetics.

I wonder aloud why these monasteries were built in the first place and why anyone these days would want to return to such a medieval way of life. “You’ve got it wrong if you’re thinking medieval,” says my companion, taking a sip of wine. “You’ve got to think Eastern.” Eastern: the fierce mysticism, that is, of Byzantine Christianity.

In the eleventh century hermits first came to Meteora seeking refuge from “the world”. Here, the caves and clefts of the forbidding rocks seemed the perfect home for those who sought to retreat from society and who strove to punish their bodies with rigorous practices so that they might purify their souls. The landscape was an exact mirror of their desire to disregard the things of earth and attend to heavenly matters.

They fasted for days and even weeks on end

Once they had found their way up the rock face and had established their niche, the hermits remained undisturbed and free to pursue God in the silence of their own hearts. They fasted for days and even weeks on end, depending on the kindness of local peasants for their meager sustenance. They went years without washing, for this was one of the signs of a holy man (and indeed these early hermits seemed to be only men): one who disdained his body so much that even as his clothes rotted on top of him he remained lost in the contemplation of the eternal, oblivious to his own stench.

In succeeding centuries, wars forced the hermits to group together for protection. In the14th century the monk Athanasius arrived from Mount Athos, the group of monasteries that stretch over a 50-kilometer peninsula jutting into the Aegean Sea southeast of Thessaloniki. With nine other monks, he established the first Meteora monastery.

Women were strictly forbidden to visit the monasteries

As at Mount Athos, women were strictly forbidden to visit the monasteries, and the monks were instructed not to give food to a woman even if she were dying of hunger. (At Mount Athos, not even female animals were allowed. Athanasius himself, his early biographer tells us, never allowed the word “woman” to sully his lips.) At the height of the middle ages, the monasteries grew in number to 24. Only three are now still inhabited: Transfiguration (Great Meteoron), All Saints (Varlaam) and St. Stephen’s.

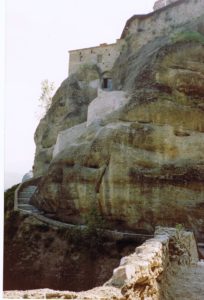

It is not known exactly how the ascetics reached their lonely habitations, or how they got the materials hoisted up to build the monasteries. The likelihood is that they hired local hunters and goatherds who were intimately familiar with the passes and crags in the rock. The biographer of Athanasius says only, “And taking a certain climber, he put him on a stone, and building a hut he remained there a long time.”

Up until the early decades of the twentieth century, men who visited the monasteries either climbed by rope ladders, which were often frayed and barely secured, or were pulled up in net baskets, swinging precariously over the abyss. Visitors were instructed to avoid dizziness by closing their eyes as the creaking pulley lifted them up, and to chant a hymn in order to keep calm through the ordeal.

Up until the early decades of the twentieth century, men who visited the monasteries either climbed by rope ladders, which were often frayed and barely secured, or were pulled up in net baskets, swinging precariously over the abyss. Visitors were instructed to avoid dizziness by closing their eyes as the creaking pulley lifted them up, and to chant a hymn in order to keep calm through the ordeal.

In 1920 the monks began cutting steps into the rock leading up to the buildings, and in 1948 a paved road was completed, making the still-inhabited monasteries accessible by car. In the same year, permission was granted for women to visit the monasteries. (In these matters Meteora has surpassed Mount Athos in modernization. At the entrance to the Holy Mountain, as Mount Athos is called, a sign still stands forbidding women to enter. Up until the late 1950s, wheeled vehicles were also forbidden, the only access to the Mount Athos monasteries being by foot or mule. The decision to build roadways still remains a controversy among some of the monks. Apparently no such controversy has yet arisen regarding the ban against women visitors.)

St. Stephen’s, a “nunnery”, or monastery for women

In 1961, St. Stephen’s, the oldest monastery and the only one visible from the road below, became a “nunnery”, or monastery for women. It is the most accessible of the monasteries; an eight-meter footbridge over the chasm brings the visitor face to face with the monastery’s imposing iron door which opens onto a sunny courtyard, the stark austerity softened by the presence of azalea and bougainvillea bushes and flowering plants in earthenware pots.

This is the peaceful setting where the spiritual quest takes place in the stillness and solitude of the heart. Here, nuns of all ages–a surprising number of them young, with smooth complexions and sparkling eyes–labor with rolled-up sleeves and easy smiles. A nearby plaque, however, refers to “the church of Christ” as the “new ark” that is saving the world from the “cataclysm of sin”. The pleasant courtyard and happy faces can be deceptive: there is nothing sunny about the work that is carried out here.

This is the peaceful setting where the spiritual quest takes place in the stillness and solitude of the heart. Here, nuns of all ages–a surprising number of them young, with smooth complexions and sparkling eyes–labor with rolled-up sleeves and easy smiles. A nearby plaque, however, refers to “the church of Christ” as the “new ark” that is saving the world from the “cataclysm of sin”. The pleasant courtyard and happy faces can be deceptive: there is nothing sunny about the work that is carried out here.

That work, here on a spot suspended between earth and sky, is nothing less than a lifetime spent in contemplation of the eternal–or, in other words, an inner search for what is essential and lasting. To carry out this quest, one leaves one’s place of comfort and moves to a barren land where outward distractions have been left behind and the interior struggle begins.

Anyone who has been on such a desert quest will tell you that the experience demands a healthy respect, and it is not to be undertaken lightly. In the tradition of Byzantine Christianity, the search is carried out within the context of liturgical prayer, where one prays with the whole body, chanting, bowing, signing oneself with the cross, gathering in spirit the whole of humanity.

We leave Meteora on a Sunday morning, driving past a church where men in well-pressed suits congregate outside, smoking cigarettes. No women are in sight; they are perhaps already inside, lighting tapers and placing them in a vat of sand at the back of the church. They too will pray with their bodies, moving about the church, bowing in front of icons, lighting more candles, moving their lips in prayer as bearded clerics in gold brocade vestments chant the prayers of the sacred liturgy.

Their sisters on top of the monastic rocks continue their lives of unceasing prayer. For them, Sunday is a solemn feast, and this means that there is more than the usual amount of liturgical prayer. There will be more chanting, more bowing, more lighting of candles. All that can be said, perhaps, of this stark way of life is that here there is a spiritual continuity, a sense of ageless prayer, a desire for goodness–and that humanity’s attempts to transcend itself are limitless and mysterious.

—Review for Religious, No. 69, 2010