14 Nov ‘Un Petit Saint’

In 1946, two years before Thomas Merton’s book The Seven Storey Mountain brought Trappist monasteries into popular focus, a twenty-one-year-old man set out on a ship from France to try his vocation in one of them. His destination was the Abbey of Notre-Dame du Lac in Oka, Quebec. His name was Georges Vanier, named after his father, who was the Canadian ambassador to France.

Georges Vanier Sr. had been named to the diplomatic post in Paris in 1939 as Europe was preparing for war, and the family escaped to England when France fell to the Germans in June 1940. They returned to Canada, where Vanier Jr., the second of five children and the oldest boy, finished his schooling summa cum laude at Loyola College in Montreal. In 1944 he joined the Canadian army and was in Georgia training for the Pacific battle when the war ended.

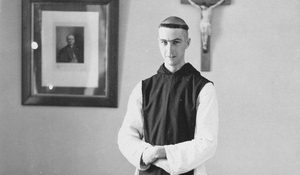

He rejoined the family in Paris a few months later. Two of his parents’ friends, the philosophers Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson, were told of the young man’s interest in philosophy, and they both offered to help him settle into further studies. When his parents learned that, rather than continuing his education, their son was returning to Canada to become a Trappist, his father asked him what his friends’ reaction would be. “They’ll think I’m a crackpot,” young Vanier replied. In December of that year, he received the black and white Trappist habit and a new name: Benedict.

“They’ll think I’m a crackpot”

Over a series of summers, I made annual visits to the Oka monastery as I worked on a biography of Benedict’s parents. His father had become the governor general of Canada, the first Roman Catholic in that position, in 1959. The Vanier couple had a deep sense of public service, fueled by a profound spiritual life. Mme Vanier’s mother as a young woman had received spiritual direction from the Jesuit Almire Pichon (the same Jesuit who had been the first spiritual director of the young St. Thérèse of Lisieux). Thus their spiritual outlook had deepened and broadened beyond the confines of Quebec Jansenism of the day. They became friends with the Lisieux Carmelites, Mère Agnes (the saint’s sister) saying to them, “You’re part of the family now.” After her husband’s death, Mme Vanier joined Benedict’s younger brother Jean at the fledgling community he had begun in France. The community, called L’Arche (now an international movement), consisted of people with mental disabilities and assistants who lived with them as a family.

At Oka, Benedict and I sat on lawn chairs beneath the spreading branches of an oak tree, he wielding a can of insect spray. He had spent the past five decades cutting slabs of cheese, sorting apples, tending bees—and, increasingly, giving spiritual counseling. When he was still a novice, his abbot had told his father that the lanky, six-foot-four Benedict was un petit saint in the making.

Benedict himself, however, wouldn’t have seen it that way. Before leaving for the monastery, he had told his parents that the Trappist life seemed “sensible”. No one told him that it was a life of penance and asceticism. On an early visit, a concerned friend from Montreal noticed a nervousness about the young monk, a reticence in his speech. “You could be disappointed,” was how Benedict put it to me.

Benedict himself, however, wouldn’t have seen it that way. Before leaving for the monastery, he had told his parents that the Trappist life seemed “sensible”. No one told him that it was a life of penance and asceticism. On an early visit, a concerned friend from Montreal noticed a nervousness about the young monk, a reticence in his speech. “You could be disappointed,” was how Benedict put it to me.

On another occasion, he told me he had entered the monastery to learn contemplation and found (like Merton) a machine. As he said this, he rolled his long arms around each other, simulating a bulldozer. Through it all—the rote work, the strict fasts, the inability to pray in the pre-dawn hours—he somehow found his way. “God wanted me here,” he told me simply. In 1952 he was ordained to the priesthood. Around the same time, after a visit to the monastery, his father wrote to a friend, “Benedict is always smiling, and when he’s not smiling, he’s laughing.”

“Benedict is always smiling, and when he’s not smiling, he’s laughing.”

I sent him the chapters of his parents’ biography in manuscript form, and he made a few suggestions. My visits continued after the book was published and the Trappists moved to a new monastery north of Montreal. Bemused by voicemail, Benedict would phone from time to time, and hesitating, say, “Is that you—or your voice?” I’m still unable to delete his last voicemail message to me. It came in January, 2014, four months before his death: a new year’s blessing on my work. “It all serves a purpose,” he said. Then he said it again, for emphasis.