20 Mar Abbaye Val Notre Dame

At six o’clock on a summer morning, the only sound outside the Trappist Abbaye Val Notre Dame is the croaking of two bull frogs in the nearby pond. The abbey, located deep inside the foothills of the Laurentian Mountains in southern Quebec, is so remote that when the monks began building, they had to forge a road to link it with the outside world.  They moved there in 2009, relocating130 kilometres north from Oka, where, a hundred and twenty-eight years earlier, four of their monastic forebears had landed to found a monastery.

They moved there in 2009, relocating130 kilometres north from Oka, where, a hundred and twenty-eight years earlier, four of their monastic forebears had landed to found a monastery.

The four monks had travelled from Bellefontaine Abbey in France and arrived at the hilly, densely wooded area near Lac des Deux Montagnes and the village of Oka, west of Montreal, on 26 August 1881. They had been invited by the bishop of Montreal and were warmly encouraged by the Sulpician Fathers, who offered them a thousand acres of land.

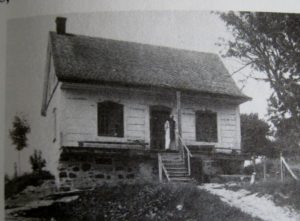

The only dwelling available was a small miller’s cottage

Warnings in transatlantic letters, however, had preceded the monks: the land, generous gift though it was, consisted mostly of rock and trees; if the monks practised the same physical austerities as those of Bellefontaine, such as living in an unheated building, the fierce Canadian winter would kill all the monks by February; the prospect of novices seemed dismal, because although the province of Quebec was French and devoutly Catholic with large families, the overall population was still relatively sparse.

(Canada, after all, was still a young country, four provinces having been joined in federation by an act of Westminster, known as the British North America Act, fourteen years earlier.) Moreover, the only dwelling immediately available to live in was a small miller’s cottage.

The monks were undeterred. They laid straw mattresses on the cottage floor as bedding and immediately set up their monastic schedule. Local priests and farmers brought gifts: a cow, a plough, a wheelbarrow, garden produce. By mid-November they were in their new, roughly built, monastery, up the hill from the miller’s cottage.

Little more than a year later, during which they had endured not only the cold of winter but also, through open and unscreened windows, the mosquitoes of summer, they were joined by two postulants from the local area.

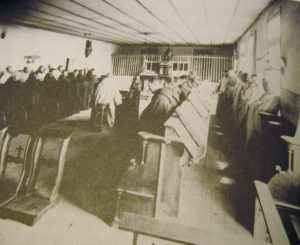

As the monks hacked down trees and cleared away rocks in an effort to establish a farm, they maintained their monastic routine—rising at 2 am, keeping strict fasts, spending the usual amount of time in meditation, praying the divine office and celebrating Mass. The only concession to the unusual harshness of their manual labour was an obligatory piece of bread dipped in coffee each morning before they started out for the woods with axes on their shoulders.

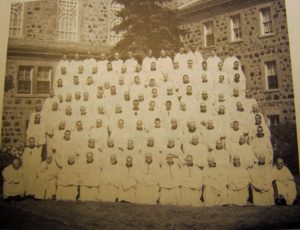

Against all odds, the Trappists thrived in the fierce conditions. By the turn of the twentieth century the collection of monastic buildings had become known as the Abbey of Notre-Dame du Lac. The community had grown to over seventy in number, with yearly crops and over a hundred farm animals.

The monks had succeeded so brilliantly in their endeavour that they were pressed into beginning an agricultural school for orphans in the area: an enterprise that throughout the decades of its existence would continue to challenge the essential Trappist vocation of silence and contemplation.

Most important–for the historic reason that it proved a gold mine for the still-struggling abbey and over many decades has put the name “Oka” on the gastronomic map–came the arrival from France in 1893 of a Trappist brother who was skilled in the art and craft of making Port-du-Salut cheese (named after the French abbey where it originated).

This monk, named Brother Alphonse Juin, was such an expert at the cheese-making process that, given the primitive means by which he set up his operation at the Oka monastery, he needed only to dip his finger into the pot to know when the mixture was to be taken from the heat.

With the first two decades of the new century came the scourge of many wooden structures: one fire after another destroyed all the monastic buildings. The main building, the monastery itself, was rebuilt in 1918.

From then on, the monastery continued to flourish. A school of veterinary medicine joined the agricultural school. The cheese factory expanded. The number of monks rose to nearly two hundred. As a reminder of their origins, they moved onto the monastery grounds the small miller’s house where the first monks had lived.

With the 1960s came Vatican II and Quebec’s slide into secularism.

The changes that came as a result of the Council were welcome ones: the rule of silence was modified, a shift in perspective on manual labour was made from the penitential (“a penance imposed on sinful man”) to the more wholesome notion of helping to sustain the community through the work of one’s hands. In the great abbey church, with its dome fashioned in graceful curves, the necessary liturgical changes took place.

The altar that came to be used in the 1970s was a 17th-century French ecclesiastical chest. This piece of furniture had been used originally as the altar in the chapel established in Ottawa’s Rideau Hall, the residence of Canada’s Governor General, by Georges Vanier, when he was named to that position in 1959. He remained in that office, as the first Catholic and the first French Canadian, until his death in 1967.

His widow later gave the altar to the Oka Trappists, one of whom is their son, Benedict. (After Madame Vanier’s death in 1991, the Vaniers’ cause as a married couple was introduced in Rome, but currently lies dormant. Another Vanier son, Jean, the founder of the L’Arche movement for mentally disabled adults, who lives in France and no longer travels, used to make rare visits to the abbey.)

It comes as no surprise that the monks’ decision to move from their historic location had to do with numbers. There are now fewer than thirty monks in the abbey, which is called Abbaye Val Notre-Dame. Over the decades, they divested themselves, handing the agricultural school and the veterinary school over to the Quebec government and selling the cheese factory (although the long association of Oka cheese with the abbey has remained such that the monks’ decision to relocate made news across Canada).

Their new monastery, now four years old and constructed from an award-winning design, has a Zen-like quality: all windows, straight lines and high ceilings, set in a square shape around an inner, cloistered courtyard.  Signs remind visitors to maintain silence.

Signs remind visitors to maintain silence.

In the abbey church, the wall behind the altar is made up of floor-to-ceiling windows that look out upon sky and dense woods.

The monks file in for prayer seven times a day, beginning with Vigiles at 4 am. Their farming days behind them, their manual work now consists of making chocolate, fruitcake, and other delicacies, although Oka cheese remains the centrepiece of their gift shop.

Signs remind visitors to maintain silence.

Compline, night prayer, ends the day at 7:30 pm. In high summer, the sun shows no sign of setting as the monks face each other in their stalls against the backdrop of all outdoors. When they turn to face the statue of Mary, the chapel’s only image, their voices gather strength with the final chant of the day, the solemn Salve Regina.

I see these monks year after year, and as always, some are greyer and more bent this summer than last. I am overwhelmed by their fidelity to this their hidden work as they stand on the shoulders of those tough and holy men in whom the punishing Canadian wilderness met its match. As the chant winds down–“O clemens, O pia…”–I pray to be somehow drawn into this fidelity, this divine work, beyond my own feebleness, to be gathered in with this small section of the communion of saints.

—published in Catholic Life, March 2014

(Benedict Vanier died on May 13, 2014.)