08 Apr The Jesuit Who Reinvented Poetry

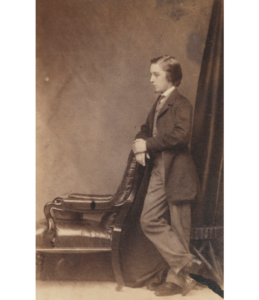

Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1879

In December 1918, a ninety-seven-year-old widow by the name of Catherine Hopkins, received a modest volume of poetry with a simple blue cover. The title was Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

The book, prepared and edited by England’s Poet Laureate, Robert Bridges, was dedicated to her. The dedication, written in Latin, indicated in part that the book was “a memorial, though late, of her beloved son, a poet awaiting the praise due to his genius.” Bridges himself was seventy-four, the same age Hopkins would have been had he still lived.

Hopkins had died nearly thirty years earlier at the age of 44. He and Robert Bridges had been close friends ever since they’d met as students in Oxford in the mid-1860s, both having become attracted to the High Church Anglican movements that were swirling around the university town at the time.

After finishing with a double first in Classics at Oxford, Hopkins felt drawn to religious life and faced a further choice: Benedictines or Jesuits. After consulting Newman about the Jesuits, he received this reply from the saintly priest: “Don’t call ‘the Jesuit discipline hard,’ it will bring you to heaven.” Hopkins had written poems ever since childhood, and in an act of asceticism before entering the Jesuit novitiate, he burned them, resolved to never write poetry again.

But his life as a poet was revived when, during a snowstorm on December 6, 1875, a ship called the Deutschland struck a sandbank in the Thames Estuary en route to New York City. Among the people who drowned were five German Franciscan nuns who were fleeing the anti-Catholic laws enacted in Bismarck’s Kulturkampf. At the time, Hopkins was studying at the Jesuit theologate called St. Beuno’s, in Wales. The double tragedy of the five nuns’ exile and then death seemed particularly grievous, and Hopkins’s rector expressed the wish that someone would write a poem about the accident and the deceased nuns.

Hopkins as an adolescent

This proved to be a watershed moment for Hopkins. The result was the long ode “The Wreck of the Deutschland”, the work that ushered in the wild creative strangeness of his mature poetry, and it is now considered Hopkins’s masterpiece. At the time, no one could understand the poem, the Jesuit magazine The Month rejected it, and even Bridges, with whom Hopkins began exchanging poetry, disliked it, writing some time after Hopkins’s death, “I wish those nuns had stayed home.” But “The Wreck of the Deutschland” and Hopkins’s subsequent poetry prompted a later critic to declare, “[Hopkins] succeeded in breaking up, by a kind of creative violence, an outworn convention. He brought poetry forward by taking it back—to its primal linguistic origins.”

Hopkins was ordained a priest on September 23, 1877, and on the surface it’s hard to say that his priestly life was anything but a failure. At the time of his conversion to Catholicism, Hopkins’s father had lamented that his son was “throwing a pure life and a somewhat unusual intellect away in the cold limbo which Rome assigns to her English converts”. His son’s experience of the Jesuit priesthood seems indeed to have been a waste. For seven years he was sent to various Jesuit parishes throughout Britain, staying a few months here and only a matter of weeks there, with intermediate periods spent teaching Classics at Jesuit schools. Part, or perhaps most, of the inability for Hopkins to remain long in any one place seems to have been what others perceived as eccentricities and what he himself despairingly called “singularities”.

He remained innocent and guileless in many ways in spite of his high achievement at Oxford. A climber from childhood, he could be seen climbing trees, poles and buildings at unlikely times and in dangerous situations, and like a child he became transfixed by sightings that particularly struck him, as (and one can imagine the hilarity among his fellows) the pattern made by urine that had frozen against the wall of an outdoor latrine.

The example of a practice sermon, given when he was still a theology student, shows the kind of preoccupation with minutiae that could get him into trouble as a preacher: speaking on the gospel miracle of the loaves and fishes, Hopkins set the stage by describing the Sea of Galilee, which he said was shaped “like a man’s left ear; the Jordan enters at the top of the upper rim, it runs out at the lobe or drop of the ear.” The anatomical analogy continued, and as he made his way through the sermon by way of such fixations, his fellow students began rolling with laughter. Once, as a priest, he used the word “sweetheart” in a sermon, prompting a higher superior to insist that his sermons receive approval from the pastor before being delivered.

Hopkins in 1888, the year before he died.

And then there was Dublin. In 1882 the Jesuit president of the Catholic University of Ireland asked for a Jesuit from England to fill the Classics chair. The English provincial refused to send the Jesuits whom he called “the cream of the community”, and this left Hopkins as the only eligible possibility, although in offering Hopkins to the Irish post, the provincial warned that he was doing the university “no kindness in sending you a man so eccentric.” In a further letter, however, he softened his opinion of Hopkins: “Sometimes what we in the Community deem oddities are the very qualities which outside are appreciated as original and valuable.”

“Dublin…is a joyless place,” Hopkins wrote to Bridges, and his relationship with the city and the country, with a few happy exceptions, deteriorated from there. At the university he not only lectured (and this somewhat unsuccessfully), but he was also responsible for setting and marking nation-wide examinations. His own health, never robust, declined, and he complained of headaches and endless fatigue. As these years progressed, a tendency to melancholy, which had been with him all his life, deepened and, at times, seemed to disintegrate into “something like madness”, he wrote to Bridges. He became sick in the spring of 1889 and never recovered, dying of typhoid a few weeks later, on June 8.

A bleak end to Hopkins’s life, but what, then, of his poetry? Was his father’s anguished prophecy correct—had Hopkins been consigned to a “cold limbo”? It may have seemed so during Hopkins’s two years in dismal Liverpool among poverty-stricken Irish immigrants where he felt pastorally useless, yet that is where he composed two of his most affecting poems: “Felix Randal”, about the dying of a young “big-boned, “hardy-handsome” workman, and “Spring and Fall”, dedicated “to a small child”, which begins “Margaret are you grieving…” and takes the child and the reader down the path to existential loss.

During the rest of his years in parishes some of his poems echoed the Ignatian motto, “To find God in all things”–“God’s Grandeur” (“The world is charged with the grandeur of God…”), “Pied Beauty” (“Glory be to God for dappled things…”)–which expressed sheer wonder at the oddness and beauty of God’s creation.

In the Marian poem, “The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe”, we see beyond the awkward title that there is something of the twenty-first century in Hopkins’s view of Mary: she is a fleshly, earthly woman, “wild”, “world-mothering”, the giver of Jesus through both her Fiat and her body. She is ubiquitous, and through her “we are wound / with mercy round and round / As if with air…”

Hopkins told Bridges that he wrote his poems for a readership of one—Bridges himself—but surely he would be pleased that down through the years, other readers, even though not understanding much of his most difficult poem, “The Wreck of the Deutschland”, have taken delight in his wordplay and extravagant expressions (“Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us…”). And that in his so-called “terrible” sonnets of his last unhappy years, which echo the biblical psalms of desolation, many readers have found solidarity with him in his face-to-face encounter with despair and bleakness (“Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee…”; “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day…”)

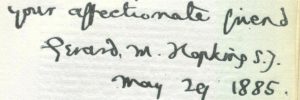

At Hopkins’s death, only a handful of people knew him as a poet, and Bridges was alone in wanting to preserve whatever he left behind. Their friendship had not only lasted through Bridges’s marriage and Hopkins’s conversion, entrance to religious life and move to Dublin, but it had flourished through clashes of opinion, misunderstandings, hurt feelings, rude brusqueness (Bridges) and querulousness (Hopkins).

A memoir planned shortly after Hopkins’s death fell through. Bridges, fearful that Hopkins’s poetry would be considered too unusual and experimental in late Victorian England, began to select a few poems for anthologies, but these were received with only polite interest.

A Jesuit by the name of Father Keating came along, expressing a desire to publish a complete edition of the poems. Bridges, who had disapproved of Hopkins’s decision to join the Jesuits and later claimed that the Jesuits had worked his friend to death, worried that Keating was interested merely in Catholic piety and had little interest in the poems’ literary value. “I do not think that Gerard wd. have wished his poems to be edited by a committee of those fellows,” he wrote.

In 1916 Bridges included some of Hopkins’s poems in a wartime anthology, The Spirit of Man, and he subsequently received numerous questions about his friend’s poetry. In September 1917, he wrote to Mrs. Hopkins, “I think that the time has come to publish the poems.” The Victorian era was long over, a new century had begun, a war was raging, Bridges’s only son had been severely wounded in battle, and his wife was ill. Bridges himself, now England’s Poet Laureate, had become a lion in winter and his friend’s mother could not live much longer. (Hopkins’s father had died two decades earlier and Mrs. Hopkins was to live another three years.)

The publication of Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins finally saw the light of day in 1918. A prefatory sonnet composed by Bridges addressed his dead friend (“…Hell wars without; but, dear, the while my hands / Gather’d thy book, I heard, this wintry day / Thy spirit thank me, in his young delight…”). The book was slow to sell, and only in the year of Bridges’s death, 1930, was a second edition published.

Now, over the past hundred years, admiration for Hopkins’s poetry has far out-stripped interest in Bridges’s own work (given his awareness of Hopkins’s genius, he no doubt knew this would happen). For Hopkins’s poetry, however, we have Bridges himself to thank.

—published in The Tablet, 8 December, 2018